Utilizing the 200-year-old technique of ‘hammered copperware,’ the seventh-generation successor that transformed it into a globally acclaimed brand

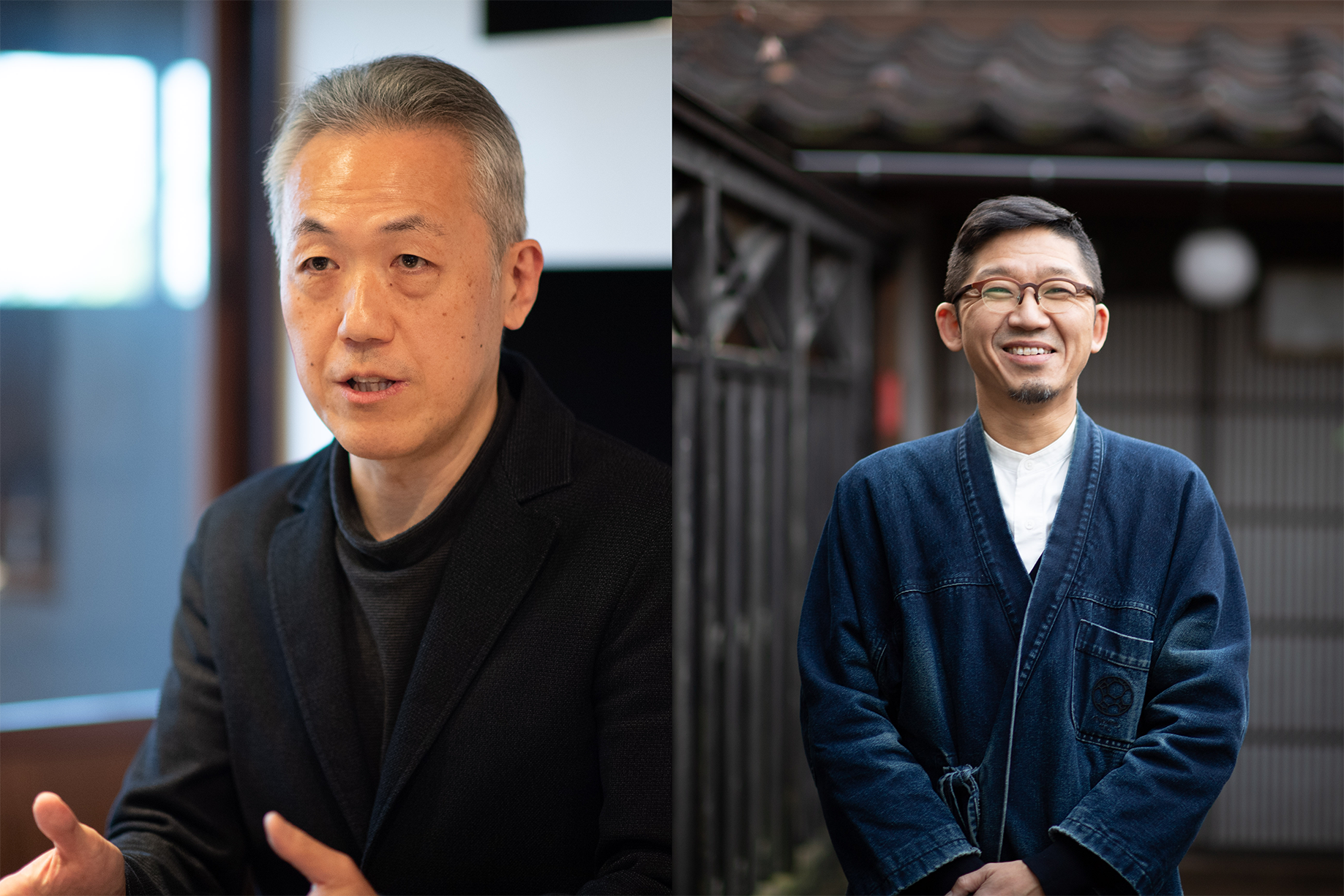

Motoyuki Tamagawa and Ryu Yamada

Gyokusendo Co., Ltd.

Utilizing the over 200-year-old technique of hammered copperware (Tsuiki Douki), revolutionized sales methods and transformed Tsubame-Sanjo into an international industrial city.

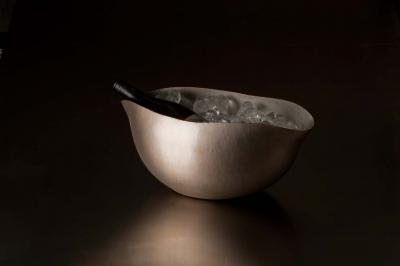

Niigata Prefecture’s Tsubame City is known as one of Japan’s leading “manufacturing towns.” Since the Edo period, the metalworking industry has flourished here, and traditional techniques are still being passed down to this day. Founded in 1816, Gyokusendo is a long-established maker of Tsuiki Douki (hammered copperware), crafted by shaping a single sheet of copper through hammering. Starting in 2003, Gyokusendo began expanding overseas by exhibiting at international trade fairs, including one in Frankfurt. Their collaboration with KRUG, a Champagne maison under the LVMH Group, on a custom-made wine cooler garnered worldwide attention. Currently, 90% of their sales come from directly managed stores, with 50% of these purchases being made by inbound foreign tourists, attracting customers from both Japan and abroad. To preserve traditional techniques, Gyokusendo continues to innovate without being bound by conventional thinking, staying true to the path they believe in.

Chapter.01 The seventh-generation’s distribution reform to revitalize a long-established company that had fallen into the red.

Founded in 1816, Gyokusendo has preserved the art of Tsuiki Douki (hammered copperware) for over 200 years, crafting pieces by hammering a single sheet of copper. Their advanced technique of seamlessly forming kettles from a single copper sheet and their unique method of applying various colors to copper, which is rare even globally, have been designated as Intangible Cultural Properties by both the Japanese government and Niigata Prefecture.

Their brand message is “To Strike. To Strike Time.” In the workshop, the rhythmic sound of artisans hammering copper resonates like a symphony. The most captivating aspect of Gyokusendo’s hammered copperware is its “aging beauty.” The products, strengthened by hammering, are highly durable and gradually change color as customers use them in their daily lives. The transformation varies depending on how they are used, making each piece truly one-of-a-kind. For Gyokusendo, “beauty” is crafted by the artisans’ hammering and nurtured over time by the customers who use the products.

Today, Gyokusendo operates its own stores in Tsubame City, Niigata, as well as in Ginza and Nishiazabu, Tokyo. 50% of their sales come from inbound foreign tourists, attracting a global clientele. However, when the seventh-generation successor, Motoyuki Tamagawa, took over as president in 1995, the company was facing a severe crisis. The demand for their primary products—corporate gifts—had plummeted, leading to financial losses and even the necessity to lay off employees.

“When I inherited the business, my sole purpose was to protect the remarkable hammered copperware techniques that had been passed down for over 200 years. To achieve that, it was necessary to fundamentally change the traditional management and distribution systems,” says Tamagawa.

His first step was to shift from the conventional wholesale distribution model to direct sales, allowing Gyokusendo to communicate the value of its products directly to customers.

“We needed to create new products to replace corporate gifts, but through wholesalers, we couldn’t hear our customers’ voices, leaving us unsure of what to produce. This was our biggest challenge. It required immense determination to break away from established business practices, but I was able to make bold reforms because my father, the sixth-generation successor, trusted me completely, saying, ‘I leave everything to you,’” recalls Tamagawa.

He personally visited department stores nationwide, conducting live demonstrations at events. Through conversations with customers, he gathered valuable insights that led to the creation of popular products like the Guinomi (sake cups) and the Beer Cup, which remain best-sellers today. As sales increased, even the artisans, who were initially skeptical about live demonstrations, began actively participating.

By showcasing the manufacturing process and conveying the product’s value firsthand, Gyokusendo established a direct sales model, crafting products that reflected customer feedback and strengthening the bond between the artisans and their clientele.

Chapter.02

From department store sales to direct management.

From market-in to product-out.

Continuously evolving to meet both domestic and international markets.

While expanding sales channels to department stores nationwide, Motoyuki Tamagawa was already setting his sights on international markets. As a first step towards entering overseas markets, in 2003 he participated in the “Hyakunen Monogatari”[1] project organized by the Niigata Industrial Creation Organization (NICO) and exhibited at trade fairs in Paris and Frankfurt.

“At the time, I believed that our products would resonate with the European market, so we designed wine coolers, glasses, cutlery, and other items with a Western audience in mind, intending to expand our presence through international trade fairs,” Tamagawa recalls.

However, in Europe, copperware was widely regarded as an everyday item with low-cost alternatives, making it difficult for high-priced, artisanal products like those of Gyokusendo to gain traction. Unexpectedly, though, demand from Greater China began to grow steadily.

“In Greater China, there is a rich culture of enjoying tea, and customers perceived copperware not as practical items, but as luxury goods. Realizing this, we shifted our perspective from targeting specific countries to focusing on lifestyle categories—tea, coffee, sake, and flowers. We encouraged our artisans to become experts who could confidently present their best creations, enhancing the Gyokusendo brand by directly communicating its value to customers,” says Tamagawa.

Increased participation in international trade fairs also paved the way for collaborations with overseas companies. Notably, in 2011, Gyokusendo partnered with KRUG, a Champagne maison under the LVMH Group, to create a functional and stylish wine cooler. This exclusive product is now used in high-end restaurants and bars in France and Japan.

Through this collaboration, Tamagawa was deeply moved by visiting KRUG’s vineyards and winery, an experience shared by the sixth-generation successor of KRUG when visiting Gyokusendo’s workshop. This emotional exchange inspired Tamagawa to pursue further reforms.

“I was moved to tears when I visited KRUG’s vineyards and winery. Likewise, the sixth-generation head of KRUG was also moved to tears during his visit to our workshop.

When I learned that people from all over the world visit KRUG’s winery, I envisioned Gyokusendo having its own stores where customers from around the world could visit and experience the value of our products with all five senses.”

This realization led to a strategic shift from selling at department stores to focusing on directly managed stores. In addition to the flagship store in Tsubame City, which is attached to the workshop, Gyokusendo opened stores in Aoyama in 2014 and Ginza in 2017.

“When products are wrapped in department store packaging, customers buy them based on the department store’s reputation. We want to build that trust ourselves,” explains Tamagawa.

Shortening the distribution channel became a key branding strategy, and Tamagawa’s reforms continue with the aim of attracting even more customers to their directly managed stores.

[1] Niigata Hyakunen Monogatari:

A project planned and managed by the Niigata Industrial Creation Organization (NICO) to build an international brand from the region that will last 100 years for the succession and continuation of technology.

Chapter.03 Transforming Tsubame-Sanjo into an “International Industrial Tourism City” that attracts visitors from all over the world.

During his visit to KRUG, Motoyuki Tamagawa discovered that Champagne-making had been transformed into a tourism resource, attracting visitors from around the world who toured the vineyards and enjoyed stays at the auberge. This inspired him to come up with a new vision: to transform Tsubame-Sanjo into an “International Industrial Tourism City.”[2]

Gyokusendo’s ambition aligned with local government initiatives, leading to the launch of the “Tsubame-Sanjo Factory Festival” in 2013. This event opened local factories to the public, allowing visitors to observe and experience the manufacturing process firsthand, thereby promoting industrial development and tourism.

In its inaugural year, the festival featured 54 participating companies and attracted over 10,000 visitors. To further boost international engagement, exhibitions were also held overseas in Milan, Taiwan, Switzerland, and London, actively drawing visitors from around the globe.

Ryu Yamada, Gyokusendo’s manager responsible for sales and business strategy, served as the executive committee chairman several times for the event. Since its inception in 2013, the festival has been held annually, attracting 109 companies and 38,592 visitors in 2024, with 42% coming from outside Niigata Prefecture. It has gained national attention as a successful example of industrial tourism.

Reflecting on the festival’s success, Yamada explains,

“The biggest success factor was the three-way collaboration between the government, local private companies, and a team of creative professionals. To engage a diverse range of stakeholders, we focused on ‘translating’ the purpose and significance of the initiative so that each group could understand it from their own perspective.”

Another factor contributing to the festival’s success is the region’s unique industrial identity.

Tsubame and Sanjo are known for producing tableware, kitchen utensils, hoes, and plows, which are closely connected to food and agriculture. This made it easier to collaborate with farmers and restaurants for tasting sessions and harvesting experiences, enhancing visitors’ sense of familiarity and engagement.

Encouraged by the festival’s positive impact, around 30 companies now conduct open factory tours year-round. Inspired by this, Yamada established a separate company to develop tours that position local factories as key tourism resources.

Looking ahead, Tamagawa envisions the construction of facilities like a Tsuiki Douki Museum and an auberge to let visitors fully immerse themselves in Gyokusendo’s world. His ultimate goal is to make Tsubame-Sanjo a destination that attracts visitors from all over the world, so his journey of transformation continues.

The festival also attracts a significant number of young visitors interested in craftsmanship, addressing the industry’s challenge of succession and skill transfer. Despite only recruiting through their website, Gyokusendo receives 30 to 50 applications annually, with 80% of applicants being women. Currently, 21 artisans are actively working at Gyokusendo, ensuring that traditional techniques are securely passed down to the next generation.

[2] International Industrial Tourism City:

A city that leverages its unique local industries as tourism resources to promote tourism development.

Tsuiki Douki (hammered copperware) is crafted not through a division of labor but by a single artisan who handles all stages of the production process. At Gyokusendo, the workshop is open after regular working hours, from 5:30 PM onwards, allowing artisans to practice their skills, create their own pieces, and nurture their artistic sensibilities.

To celebrate its 200th anniversary in 2016, Gyokusendo introduced the Gyokusendo Hallmark system[3]. In addition to the traditional logo and the zodiac sign of the production year, a third stamp representing the artisan’s personal mark is now added to each piece, indicating who made it and when. This not only facilitates maintenance but also preserves the spirit and craftsmanship of the artisan for centuries to come.

Gyokusendo cherishes the concept of “Aging Beauty.”

Just as their copperware gains character and strength over time, the company itself has evolved, refined its charm, and grown stronger through the vision and dedication of successive generations of leadership. The future of Gyokusendo and the aging beauty of Tsubame-Sanjo are truly exciting to behold.

[3] Hallmark:

A stamp used to certify the quality of precious metal products.

Written by: Mari Kanematsu

Interview Date: December 20, 2024

Please note that the content of this article is based on information as of the interview date.